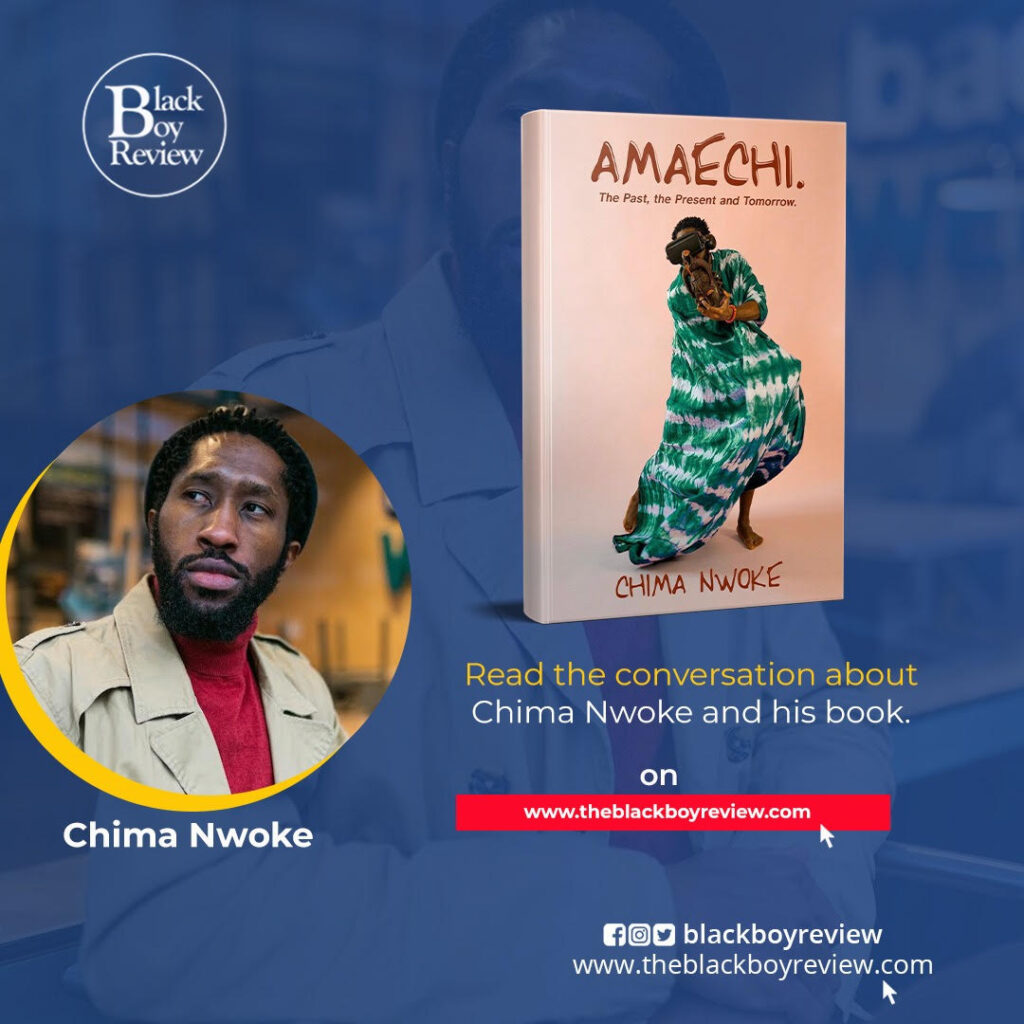

Chima Nwoke is from Umuaka in Imo state, Nigeria. He grew up on the campus of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka and studied Engineering from the university. He is the co-founder of Dinta Media, an outfit dedicated to telling the best stories of Africans and Africa. He is currently studying Information and Communication Design in Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences and lives in Essen, Germany.

So Chima, I’m going to spend time on the cover design of your collection? Can you tell me about the motivations? What inspired them? I see that they are photographs of you in another form. Can you tell me everything about that cover design?

Thanks so much for the question. As the subtitle suggests, the stories progress from the past to the present and the future. From the onset, it was intentional to create a cover that would try to convey that. I played around with different concepts in my head but ultimately settled for the one I used. It features me draped in a tye-dye bedsheet, wearing a VR headset and holding an African traditional mask. The mask is supposed to represent the past or where we’re coming from, while the VR headset depicts the future or where we’re headed. On this project, I like to consider myself as Tyler Perry (who writes, produces, directs, executive produces and also plays multiple characters in his films) as I wrote the stories, directed the cover art, designed the cover, featured on the cover as a model and also designed the layout of the book.

How do you come up with chapter names? I found that spectacular in your collection. Each chapter for me has a name that was either too relatable or special.

About the titles of the stories, there wasn’t any particular process. For some, I had the titles in my head then I had to create stories around them. Examples are stories like ‘Juju Heist’ and ‘The day I die.’ For some others like ‘Low Budget Sherlock Holmes’ and ‘We Shall Come Again,’ I had the story concept or idea and had to figure a title out either from characters’ dialogue or actions. The relatability came as a result of the voice in which the stories were told and I also tried to incorporate some pop culture references into them as well.

Exploring African traditional beliefs is usually a “not-easy” writing task, and you do this effortlessly in a way that it is simple. Young people run away from this though, but I liked how you bring it up. What would be your major experience in writing about this?

I’ve always strongly believed that in order for us to know where we’re going, we need to know where we’re coming from. That has been one of my major motivations for promoting the Igbo culture and traditional beliefs. I’m a Christian. I was born into a strong Roman Catholic family but in the past couple of years, my focus has been more on spirituality than religion. However, if we’re being honest with ourselves, Catholicism (or Christianity for that matter) is not ours. Our forefathers and ancestors didn’t know what it was and the Ọdịnaala they practiced worked for them. For me to approach the subject matters and themes explored in the collection, I had doubts because I felt I wasn’t the right person to tackle some of the issues. So, it was important for me to tell the stories from the perspective of a researcher, and to also see if there are any similarities between the religious practices. I don’t know all the answers. I don’t even think I know any answers because it’s all very deep. I want, or rather, I hope the stories will spark conversations about our history, heritage and culture.

And then, Africanfuturism – one of your thematic structures in the collection. What has been your idea about this? And then the process of writing about it?

Like I mentioned earlier, it was intentional from the onset to tell the stories from the past to the present and then the future. Now, the future is vast and open-ended and can be interpreted in any number of ways, but I decided to place some of the futuristic stories within the African and Igbo context. I also decided to mesh our traditional Ọdịnaala practices into science fiction concepts because our ancestors achieved a lot with Ọdịnaala and even some of the science/medicine they practiced had its roots in the religion.

How long did it take you to finish up the collection?

I started writing the stories in 2020 and finished in 2022. It took about two years.

Who are your best authors? Do you like to sound like anyone? Do you easily get influenced by the people you read?

My favorite author of all time is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. She has done more for contemporary African literature than anyone alive. Also, coincidentally (or not), my favorite novel is her ‘Half of a Yellow Sun.’ I’ve read the book multiple times. I also love Nnedi Okorafor’s writing. Her work in the Africanfuturism genre is quite inspiring. I was a voracious reader as a kid. I read any and everything I could get my hands on. I drew inspiration from many of the books I read while writing my book (Authur Conan Doyle, James Hadley Chase, Mary Higgins Clark, to name a few). However, I believe in my own voice. It was important to me to maintain my own style throughout the book.

What would you like to be writing next?

For now, there are quite a number of projects in the pipeline. Many of the stories in ‘Amaechi.’ are supposed to serve as stepping stones for more bigger projects. I’m not going to give much away, but you can expect to see some of your favorite characters in future books.

You can purchase and review HERE