I enjoy writing poetry of family. Each person in my life once, and is still serving their importance. These women are my revolution. Their love, their tenderness & kindness, the way they blossom, their imperfections, & impatience, everything deserves to be documented. They run a river in my life & I swim. There is no need to politicize the representation of people in one’s life when they are the sun you wake from, the moon that pats you to sleep.

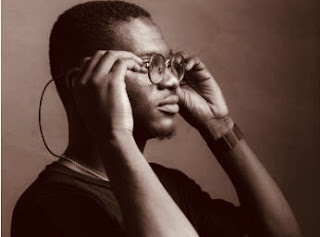

Interviewer: Ese Emmanuel

Interviewee: Adedayo Agarau

Hello, Adedayo. You are the much celebrated author of the books “For Boys Who Went” and more recently “The Arrival of Rain”. How would you say that writing poetry has influenced your view of the world, and the way you interpret experiences?

When the spirit of the Lord hovered over the first piece of this world, & saw that it was without form, words were spoken. This is the same thing that poetry does, it edifies the world from inside out. After each word turned into each piece of creation, there was an establishment of form. Poetry lets me establish a form, my form of this world. I grew from this boy whose world tendered himself with how a country affects his family, to writing about the interrelationship between depression, loss, anxiety & country. Poetry allows me to speak for myself about a cruel world. A man lynched for being queer is deserving of a tribute. A boy whose head was hacked during an election is also my head rolling off the gallow. Poetry takes a stance, turns me into anything, everything. It is also the imagination of form.

In “The Arrival of Rain”, we see an interplay of multiple themes, mostly surrounding your own experiences- very much observed in your “self-portraits”. This, perhaps, is regarded by most people as confessional poetry. In a generation rife with identity and existential crises, what role do you think the poem plays as a confessional tool, and do you think there is also a necessity for the transcendence of self- or is self-expression simply enough?

Going beyond the self now: from your books, one can see an exploration of nationhood, and nationality. Is this sense of social responsibility (encompassing the idea of a flawed nation, and beyond) something you are very much invested in, and do you see your poetry- and poetry in general- as a valid and visible means of bearing witness to the brokenness the Nigerian society? If so, beyond witness, is there a way that poetry serves as an attempt to fixwhat is broken?

Thank you. We cannot take away the concept of body from the idea of nationhood. A country is body, reminds me of Dami Ajayi’s book, A Woman’s Body is a Country. Bodies are meant to be cared for. Every form of art is a valid form of protest, a valid form of expressing ache. Niyi Osundare wrote Not my Business

& that work is still very relevant today. My poetry seeks to imagine a country as bodies, addressing each aching part, one after the other. Daniel Usman was killed during an Election in Kogi. Another boy was killed in Ibadan. Everywhere in this country, guns are tearing dreams away from mothers. Fathers are rushing into the woods for safety. & in a country where no one is safe, my body protests through its poetry. I bleed the way someone’s mother bleeds, the way a head smothered by a bullet would. Warshan Shire’s work, Home, quietly teaches how to document the brokenness of a country, how war & insurgency are capable of dehumanizing the concept of country as body:

your neighbors running faster than you / breath bloody in their throats / the boy you went to school with / who kissed you dizzy behind the old tin factory / is holding a gun bigger than his body / you only leave home / when home won’t let you stay. How else does one tell of brokenness but by showing how broken it is?

However, every form of protest has been rendered incapable, unuseful by this administration. I do not even think that the leadership reads anything. It is a mockery to think that a poem can save a country & that fact is disheartening.

Throughout your chapbook, The Arrival of Rain, we follow through a procession of the women in your life: grandmother, mother, sister, lovers- even while retaining the male perspective. This largely visible female presence, do you think it serves a “higher purpose” in your poetry, or is it simply reflective of your human, if male, experience just as everything else?

I enjoy writing poetry of family. Each person in my life once, and is still serving their importance. These women are my revolution. Their love, their tenderness & kindness, the way they blossom, their imperfections, & impatience, everything deserves to be documented. They run a river in my life & I swim. There is no need to politicize the representation of people in one’s life when they are the sun you wake from, the moon that pats you to sleep.

The title of the chapbook: The Arrival of Rain, is an enigma; considering that it expresses in a profound manner, a simultaneous memory of and longing for the seemingly banal experience of rain- as storm, as respite from a drought. We know rain, and by association, water, to be in itself, a very strong metaphor. We also see a repetition of this idea in various poems throughout the chapbook. What is your perspective about the representation of rain in the poems?

Once the poem leaves the poet, it almost stops being his. The creative, lexical, and figurative interpretation, analysis of a poem becomes very subjective. This is why the reader is at liberty to almost make of the work that they make of it. Poetry is the creativity of multiple possibilities. I must confess, rain (as a word) is one of my go-to metaphors for both abundance and ruin. It goes ahead to wreck, & to make fertile. In the titular work in Memento: An Anthology of Contemporary Nigerian Poetry, Salako said in his poem, Memento: Twilight sets and this poet must return / to his homestead of dreams, but this poem continues / elsewhere in my chest. The poet approves of my philosophy of metaphor that a poem never always has an end, just as his closure suggests. Rain, in most of the poems in The Arrival of Rain, was a harbinger of revelation or doom, for example, in two weeks before my birthday: a tree tormented / by rain / your name / hid the shame in my mouth, carefully setting the pace, mood & tone of the poem. In Fourth Portrait as Adedayo or the barren tree at the Mokola Cemetery: cloud raising placards against the coming of rain was a relevation of the coming wreck for the persona in the poem. The Poet takes a bit or the whole of himself & places it in his work. That is how the work blossoms. This does not discredit poetry of brilliance and imagination though. Metaphors single-handedly recreate the poem in the heart of the readers.

Was there a particularly constant mood that birthed The Arrival of Rain, or is it the product of a wide array of deep but temporary emotional states?

Wading through The Arrival of Rain again, I considered the book as eternally relevant. Someone’s lover will someday leave. The feeling of inadequacies still creeps through someone. A father does not return home. A grandmother dies. Another child is gunned down by the Police. We are still somehow between a raging past & an uncertain future. At this point, the book would no longer care about the writer’s mood but the relevant topics the book embodied. That is the hope at this point. Loss, and absence shared batons in the works in The Arrival of Rain, they led the poems through and through.

Moving from The Arrival of Rain now, we know that you edited the now widely popular Memento: an anthology of contemporary Nigerian poetry. What did this project mean to you, and how do you feel about the poetry- and more broadly, literary- scene in Nigeria?

Memento was born out of the need to represent the Nigerian contemporary poetry at a time when Poets like Gbenga Adeoba, Aderibigbe Damilola, Agbaakin Jeremiah, Itiola Jones, Daisy Odey are constantly taking the global map. The project seeks to amplify Nigerian Poetry as uniformly as possible. The Nigerian poetry landscape is a fecund one, blessed enough to carve out an entire movement and that was what my team and I sought to do with the anthology. We hope that it would further go into classrooms as literary texts, bringing new names into focus. I read the poems with Patrick, Kolawole, Michael, and Jeremiah & I must confess, we were overwhelmed by the support of the Nigerian Poetry community, one which is waxing stronger, reaching for the cores of Africa and beyond. We are gunning at something with this project, and it is to foster an existing Nigerian Poetry community into a safe haven for emerging and established writers.

Your bio reads that you are a documentary photographer. This ability to observe and enter into the world from a different artistic perspective, do you think it influences the way you write poetry, or is it an entirely separate exploration of your artistic persona?

I started writing long before I took up photography. My grandfather was a photographer and songwriter. That being said, photography and poetry give you the liberty to imagine form. That is the relationship. When I am not standing behind the lens, I am printing imagery through poems about my grandmother.

You have a new chapbook soon to be published, with the very interesting title: The Origin of Name. For some reason, the title does bear a resemblance to your previously published chapbook, The Arrival of Rain. Do you consider this new chapbook to be a sort of furtherance into the route that your poetry has already taken, or is it an entirely new perspective? Also, is there anything else you can tell us about the forthcoming chapbook?

The Origin of Name is a work of research. It is a body of work that considers the intertextuality of names, and the concept of naming in Yoruba Land. Every work that I currently do now leans towards a larger body of work. Although themes of Loss and absence would be found in The Origin of Names, the purpose of the book is to explore the narratives sitting inside how Yorubas name their children.

Are there any poets or writers who have influenced your writing style and helped you grow your voice? Who are they? Also, what does your creative process look like?

Yes. There is an aching conversation about influences and writing processes. Every poet is a product of the works of another poet who is also a product of some other’s work. The chain of influence cannot be taken away from the work of art. Leila Chatti, Ladan Osman, Safia Elhillo, George Abraham, Kaveh Akbar are poets that I reach for. I extensively study the works of my friends too: Agbaakin Jeremiah, Nome Patrick, Adebayo Kolawole, Wale Ayinla, Pamilerin Jacob and Michael Akuchie.

My creative process is quite flexible. I plan themes within my current project, then research for exactness. Then write. My editing process is also becoming rigid because after rejection the poet is bound to consider his art, let the spirit bear witness with his that the poem is ready to sail again.

Thank you for your time, Adedayo. It was nice to have you.