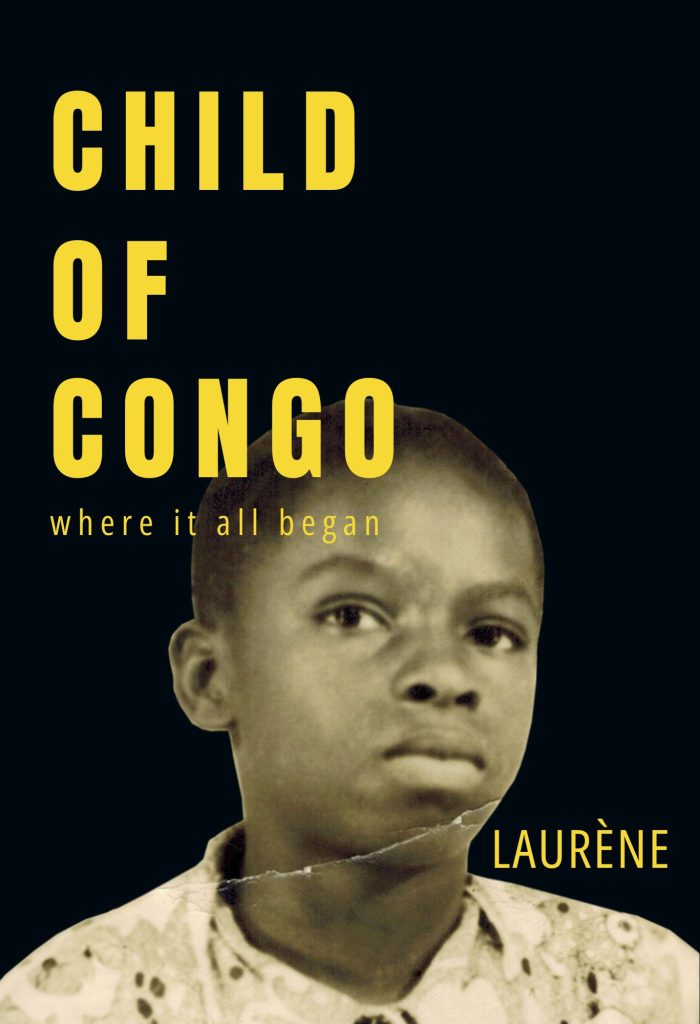

Laurène is a 25 years old writer based in Vienna, Austria of Congolese heritage. Beginning at the age of 17, Laurène used to attend the Vienna African Writers Club led by African Studies of the University of Vienna, building a strong passion for poetry. It was in 2021; however, after a spoken word performance at the African Diaspora festival in Klagenfurt that she chose to take this practice seriously. In 2022, Laurène took part in a group exhibition titled ‘An Der Schönen Blauen Donau’ to prove that poetry could both be performed as much asdisplayed. During the Vienna Design Week last year, she had the pleasure of performing as part of her second group exhibition ‘A House is Not a Home’ by curator and mentor Tonica Hunter. Perhaps her fondest moment was when Laurène attended a writer residency at Echo Correspondence until the end of year 2023 and completed her first full-length poetry book titled ‘Child of Congo’. As of late, she has been published by Brittle Paper, The Shallow Tales Review and a part of ‘African Migration Report Poetry Anthology’.

You may contact Laurène with: laurene.southe@gmail.com

Oluwalana Ajayi: You describe yourself as “a writer in every form written.” How did your journey as a writer begin, and how has it evolved over the years?

Laurène Southe: I feel like I’ve always been a writer. Writing was my tool of communication long before I found poetry. I “mangled around” lyricism for years and wrote in other forms before entering the world of poetry. People like specific titles, but “a writer in every form written” is the most accurate description of who I am.

Oluwalana Ajayi: Growing up across Austria, Switzerland and the U.K., how did those varied educational systems shape your identity and writing voice?

Laurène Southe: If I could place that experience into a box, I would say the way each educational system views history influenced me most. I spent time in five or six different systems—private and boarding schools—each with its own version of history. That taught me not to be “a crab in the bucket.” I don’t attach myself indefinitely to any European identity because there’s a bigger world beyond those communities.

Oluwalana Ajayi: You’ve mentioned struggling with verbal communication as a child and finding your voice through writing. How did writing become your primary form of expression?

Laurène Southe: I was daydreaming a lot and not outspoken. Constantly switching schools and even languages made me introverted. Writing let me articulate myself freely—especially when, as a child or because of my gender, I might be cut off or not understood in conversation. Writing gave me space to be seen and heard.

Oluwalana Ajayi: Your Congolese heritage is central to your work, yet you were raised in Europe. How do you navigate being part of a diaspora, and how does it inform your creative process?

Laurène Southe: It’s logical for me. Whatever environment I lived in, my Congolese household was the center of my being. In England, I wanted to impress the Congolese church I attended— their view of me mattered more than that of people outside my heritage. Heritage shaped me, but I also explore many other topics in my poetry and work.

Oluwalana Ajayi: “Child of Congo” began as a single poem for a Vienna exhibition before evolving into a full collection. How did that happen, and what surprised you most during the process?

Laurène Southe: It started with speaking my truth—understanding my heritage and rediscovering myself as someone who’d only visited Congo once. On Amazon, “Congo book” searches brought up only non-Congolese authors. I knew our stories belong to us.

So taking that all together in, I ventured into just a very intimate personal journey, which only got extended when I was taking a residency — two years ago now — and I really had the space and time and the means to look back into history, into my personal history, my lineage, understanding what it means to me today. And you know, what is, so to speak, my deeper purpose outside of just the individual goals that I have for myself. That collective, tribal instinct for preservation shaped the entire collection.

Oluwalana Ajayi: Your poem “Silent Genocide” addresses the crisis in Eastern Congo. What challenges did you face writing about such painful subject matter?

Laurène Southe: My parents are both from in Eastern Congo, and family there are affected by rebel groups. This history is deeply personal—it goes back beyond the Atlantic trade to the Arab slave routes. It would have been insane to talk about Congo without its struggles. That pain is part of our resilience. Resilience is brought through combat and pain, and trying to find your voice within that reality.

Oluwalana Ajayi: The collection covers Congo’s history from colonialism to present-day conflicts. How did research affect your understanding of your heritage?

Laurène Southe: It was healing. Growing up, my mother wouldn’t talk about her childhood, and my father was proud of our lineage. I lacked language, surroundings, or taste of Congo. Researching Congo—and the wider African continent—helped me know where I come from and where I’m going. I uncovered truths about neocolonialism and overlooked figures, like Tipu Tip, and recognized colonized mindsets within African communities.

Oluwalana Ajayi: You’ve said your poetry is written “through the lens of a child.” What does that perspective offer?

Laurène Southe: The poems span a decade—some as old as 2017, when I was a teenager. Self-publishing gave me full quality control and let me visualize my evolution—mindset and all. A child sees innocence and accepts things at face value, without analytics. Those fragments, when combined, form the bigger picture of this collection: the duality of Western society and a Congolese household, and the search for validation. That is what I wanted to bring forth in this poetry collection. I think, if anything, that’s the layer of this book that makes it even more special.

Oluwalana Ajayi: You’ve worked across poetry, photography, songwriting and more. How do these disciplines complement each other?

Laurène Southe: I wouldn’t call myself a photographer—it started as therapy. But essay, lyrics and poetry are connected. I came to writing through lyricism—watching MTV and listening to music lyrics as a child, turning gibberish into comprehensible lines, then essays in school, and finally poetry. I see all forms as one, shaped by different circumstances.

Oluwalana Ajayi: Who are your greatest literary influences, and how have they shaped your approach?

Laurène Southe: Mostly West African authors. I only discovered Congolese writers after finishing my book. Ben Okri’s The Famished Road and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart are top for me. Alain Mabanckou from Congo-Brazzaville is another exception. Those works taught me about African narratives, magic realism, and powerful cultural storytelling.

Oluwalana Ajayi: You attended the Vienna African Writers Club as a teenager. How important are creative communities for emerging writers?

Laurène Southe: It was close to home and welcoming for an introvert. It taught me to perform, get feedback, and speak in front of an audience—motivation for a broke student. Judges’ critiques pushed me to improve. Though I no longer attend, I’m grateful for the outlet and development it provided.

Oluwalana Ajayi: What does your typical writing process look like?

Laurène Southe: There’s no method. After finishing the book, I needed life experiences before writing again. I took a break, had new conversations, and found new material. I write at my own pace, letting life fill me first. Music still connects me—listening expands my mind, and words flow from that space.

Oluwalana Ajayi: What impact do you hope Child of Congo will have on readers unfamiliar with Congolese history?

Laurène Southe: I’m taking my book to Zurich and planning presentations in North America. I want to use my liberty to catch agents’ and publishers’ attention for a worldwide second edition. I also plan a chapbook for wider online access. My goal is to make my work familiar to everyone.

Oluwalana Ajayi: You combined your launch event with a panel on Eastern Congo’s crisis. How important is art in raising awareness?

Laurène Southe: I wouldn’t call it activism—it comes naturally. I planned the launch before February’s massacre to showcase Congo’s beauty and resilience. We served Congolese cuisine, fundraised for local organizations, and featured other Congolese authors. Art introduces identity and awareness, and if you can help, you should. I’m here because of the Congolese community’s support, so I give back.

Oluwalana Ajayi: You’ve said “the real journey begins when you act upon that unexplainable force.” What new creative territories do you hope to explore?

Laurène Southe: I want to get into visual—what I call “poetry in motion.” That means visual storytelling. Congolese cinematography often lacks female sensibility; mothers and sisters are portrayed as hard and transactional. I hope to bring a female perspective to those narratives.

Oluwalana Ajayi: What advice would you give young writers from the African diaspora connecting with their heritage?

Laurène Southe: It depends where you’re from. In South Africa, Nigeria or Ghana, foundations exist. In less popular regions like Congo, you may need to move to English-speaking countries or set up your own platforms. Most importantly, have faith in yourself and your abilities. There will be hard days, and without that belief system, it’s hard to continue. Faith is first.

Oluwalana Ajayi: If readers could take away one message from your poetry, what would it be?

Laurène Southe: I see my writing as a mirror. I observe life and personify it on the page. I want people to see their reflection—whatever emotion or action it evokes—to follow that impulse and turn the page in their own lives.