In a time when theatres face a dearth of good pieces and theatrical performances gradually fade into plain text, the need for a homecoming of the art form, its representation of the dramatic, becomes important.

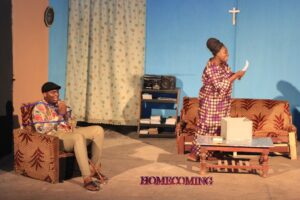

Homecoming is an unpublished play that brings to the fore, the old craft of tragic dramatic art. Written by Chetachi Igbokwe and directed by Ugochukwu Victor Ugwu. The play premiered at the New Arts Theatre, University of Nigeria, Nsukka under the auspices of the Maestro Theatre. The play, which more beautifully, is a debut, brings you closer to African art, draws you in to fear, pity, myth, and of course plunges you afresh into a communion of tragedy; that man is born broken, for he lives by mending his brokenness, and only his chi becomes his death or salvation.

The play is an Act on three characters: Nwakibe, Adannaya, his wife, and Nebeolisa, a lost son who appears to us as just Mr. Johnson; a writer from Moldova who becomes a neighbor to Nwakibe, whom he rents a room of his house. Mr. Johnson has come to write an award-winning story on the revered diviner of Umukaibe clan, Ahumareze. The climax of the incidents of the play becomes the revelation of the mark of the lost Nebeolisa.

The character of Nwakibe, Echeruo as played by Kosi, Ejikeme is sarcastic but haunted, torn between allegiance to two different religions and tethering on the precipice of madness which was almost full-blown on his gullible, but nagging wife. He comes complete with all trappings of a Sisyphean. A catechist and retired teacher, he is typically somewhere between the ‘divine and all too human.’ Like all tragic heroes, he is typically on top of the wheel of fortune, halfway between human society on the ground and something greater in the sky. His heroic acceptance of Ahumareze’s choice of a human head brings to mind the heroic acceptance which Nietzsche describes as a ‘glumly acceptance of a cosmology of identical recurrence’ and marks the influence of an age of irony which is peculiar to all tragedy, the representation of a sacrifice. Adannaya Echeruo as played by Aina Adebola, is the wife of Nwakibe, who adorns her husband with nothing but troubles with her mild insanity. She writes imaginary letters to herself from her lost son whom she claims lives at Road 314 Oxford. Johnson, Mr. writer from Moldova as played by Chimaobi Okolo, is an intelligent man often taunted by Nwakibe with his gaslighting question. A storyteller from Moldova and Azazel to the return of Nebeolisa. He is a tenant in Nwakibe’s house, whose first purpose is to write a story on the life of the great chief diviner of Umukaibe clan, Ahumareze.

On the other hand, Ahumareze, played by Simon Ebuka Ugwu, is as described by Nwakibe, a man who thinks himself a god. The chief priest of the Umukaibe clan in representation of the god of Ogwugwu. Bonded by an ancestral truce agreed by their fathers, his friendship with Nwakibe writhes in the idiom that ‘familiarity brings contempt.’

Technically, Maestro Theatre, led by the brilliant Ugochukwu, Victor Ugwu as director, has been very inventive in a lot of its productions. From the inventive use of Lapel microphones by the thespians which is a novel innovation in which seems like a traditional theatre, to the fluid and seamless blocking in all Acts, and of utmost importance, the lighting set that gave majestic ushering into each movement and manned by Tamarauketemene, Solid Freshman, to the rich eclectic props selected by the costume designer Ezinne Ugwueze, whose appropriate selection of props had the audience taken to the early 90s in the opening scene which thrills you with the stereo box in the background playing the sound of the maestro trumpeter and singer, Rex, Jim Lawson spinning you into the love trance with his song, Love AdUre , brings back a soothing rich and nostalgic past. The music director and composer, Ugochukwu Dansey Ubah’s improvisation brought a harmonized portrayal of what each scene is with the chorus serving as a pendulum that ushered in each movement like that of Dionysius’ festival in Greek writings. The chorus bringing catharsis with its soul-bending theme song without missing an inch during the ritual is symbolic to the entire reception of the performance. Although it became bothering not to notice the slow scene changes in which at some point dragged the full engagement to the audience, but this feat I had to notice, is peculiar to all traditional theatre.

In all, what I find pivotal in this play is its Peripatetic style, an experiential touch of the intellectual magnificence of the playwright demonstrated in the language of the dialogue and feisty humor, which is rare in a time when theatre performances is becoming rather strange and slowly a thing of the past, and in the need of a profound Homecoming.

Reviewer: Michael Anyanwu

Michael Anyanwu is a bibliophile, who writes when he needs to find peace with his chi. He studies English and Literature at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. His works have appeared on the Cultural weekly, The Muse, Fiction niche and elsewhere.