INTERVIEWEE: Brigitte Poirson, a former teacher and university lecturer in languages in France and England, has published seven books. A multiple award-winning poet, she has also been included in magazines and anthologies, and in “the Europe 500” and “Who’s Who in the World”. After managing and publishing the Via Grapevine poetry series in South Africa, she now promotes African literature as an editor. She offers poetry contests with WordsRhymes&Rhythm, the largest poetry platform in Nigeria and a publishing house. She occasionally organizes poetry workshops in France with a group of authors, “les Plumes Comtoises”.

INTERVIEWER: Darlington Chibueze Anuonye, a 2018 Cesar Edigo Serrano Foundation Ambassador of the Word for Nigeria, is the Director, Aba Creative Writing Workshop. He won the 2011 FECA Prize for Literature and was shortlisted in 2016 by the Ibadan Poetry Foundation for its inaugural mentoring and writing residency. Anuonye holds a degree in English Language Education from Imo State University and currently works as a temporary staff of the University of Benin, Benin City. His short fiction, memoirs and poems have appeared in Brittle Paper, Black Boy Review, Storried Magazine, Ovis Magazine, Praxis Magazine, Coal Magazine, etc.

***

Darlington: In Searching, we find. What were you searching for before you found poetry? Or was it poetry that found you?

Brigitte: Poetry found me when I started reading and writing at the age of four. Rhyming falls on very young ears like a mystic rain to sublime the daily routine. But African and Indian kids’ bedtime stories had enabled me to travel round the world. Poetry has kept chasing me round the earth, but I have never been able to catch its essence. It’s like an evanescent unicorn that flies away when you think you’re going to caress it, and the contours of its elusive body have to be redefined with every poet. I’ve chased it with my pen. I’ve chased it through the pens of others. I’m still chasing it. I once wrote, years ago, these final lines to one of my poems in French:

“And my last word was

it’s only my first”

Darlington: I understand you so well, Brigitte. From the place of private fascination to the summit of universal relevance, poetry, through its definitive form and the abundance of its affecting voices, continues to summon the spirit of humankind to participate in the making and appreciation of variety and beauty—which are the quintessence of art. I remember defining poetry as: “a means of becoming a co-creator with God”. But it was much later I realized that, in offering that defiant definition, I had taken a fortuitous voyage into the dazzling mind of Coleridge, for, without being aware of it, my words, both in conception and inference, agreed completely with his striking revelation that in writing poetry the human mind follows a divine ordering in a transcendental act of creation.

You also strike me as a disciple of Wordsworth, especially in your seamless devotion to creative peace and sanity. Where else does a disjointed soul find solace if not in the confessedly soothing words of Wordsworth that possess, among other things, an immense capacity to heal? And Wordsworth’s definition of poetry as an “overflow of powerful feelings… emotions recalled in tranquility” has enabled many poets to follow the tremors of their own feelings, even in their ungatheredness, to a point where shame is nonexistent, hoping to excavate, even if it’s for a fleeting moment, the core of all things personal and collective.

Brigitte: Certainly, Darlington. And if I had to rate poetry, I’d place it above music. Word over sound, however suggestive. Word is first and will come last. Poetry includes music. That is why I understand the man I consider the greatest French poet, Victor Hugo, when he pleaded: “Never put music on my verse”.

Darlington: Victor Hugo was one of French’s most accomplished poets, novelists and playwrights whose writings lent their unified voice to the political and social realities of his time. In what ways do you find Hugo remarkable?

Brigitte: He proved that words can rule over an empire. Napoleon III was discredited beyond recovery after Hugo wrote his Châtiments. But mostly he was able to write the equivalent of a whole novel with deep, perfect alexandrines.

Darlington: Notre Dame de Paris and Les Misérables, completed in Guernsey, are among Hugo’s profoundest writings, how did these stories affect your artistic knowledge? And did they in any way prepare you for the crucial role of discovering Hugo, the poet?

Brigitte: Les Misérables I read as a child. It contributed greatly to expand my imagination beyond limits, and it did whet my already acute sense of justice. Hugo had the knack for making his readers identify with his heroes. “I am a force that goes”, he said. (My translation of “je suisune force qui va”.) That evokes the power of poetry. Irresistible.

Darlington: Irresistible is the word. But, observably, in a bid to assert its irresistibility, poetry resists almost all things. Isn’t that amazing? Well, having realized I’m barely a rose that would wither someday, I’ve chosen, through poetry, to raise words that are abiding—giving life to even the rejects of my subterranean feelings. Do you think, like I do, that poetry is that seed of literature which grows taller and bigger than its sower?

Brigitte: Absolutely. I’ve written very disconcerting poems that explore mental zones I would have thought did not exist until words found them. It was not about putting words in feelings, but rather words exhumed what I ignored. Very often, words create themselves in my head and reveal what I was not really aware of. Expressions, associations of sounds and ideas appear all wrapped together as if they had always been waiting there. The rest is sweat. Then poetry will follow its own route. I wonder if I already mentioned to you that I consider poetry the supreme form of literature. I often make reference to that famous statement by Charles Baudelaire: “Always be a poet, even in prose.”

Darlington: Enduring and enlightening words, indeed. A substantiation of the essence of poetry. This, the poetification of prose, will heavily identify with Coleridge’s poetic vision. And if it is true that poetry is “Best words in their best order”, shouldn’t we stretch the frontiers of our talent to absorb such delightfully stimulating insight?

Brigitte: You’ve said it all, Darlington. You just echoed my own thoughts. What more?

Darlington: I see! Well, what I’m about to say now is a bit amusing, but I think it’s actually serendipitous since it leads to what I have always wanted to talk about. My sister walked into my room a few minutes ago and found me smiling, a smile driven by the vast treasures of poetry. She asked, “Why are you smiling? Chatting with your lover?” Poetry, sometimes, appears to me as lovers’ tryst, and other times as a refuge for men and women whose love is unrequited. Think of e e cumming’s terrific affection for Elaine Orr and how it inspired a colossal body of fine erotic poetry, consider how an unsuccessful but eventful relationship with Maud Gonne sharpened the power of observation, heightened the aesthetic aspiration, kindled a newer, profounder human awareness and transformed tremendously the literary fortunes of that unequaled Irish poet, W B Yeats, then you might be compelled, as I am, to think that love has a telling influence on poetry.

Brigitte: The funny thing is that e e cummings’ wife disapproved of his insistence on refusing to use capital letters in his name. But he needed his love indeed to face his poetic challenges. Of course, love and poetry form a natural couple. Unrequited love? Yes, it has produced irreplaceable poetry. But let me tell you I wrote my best poetry when I was a happily married woman. Love gave me wings. And the truth is; since my husband’s death last July, I haven’t been able to churn two words. I’m drier than the Sahara. Love is the favorite fountain of Poetry.

Darlington: You’ve touched something vital now. Do you know that Maud Gonne’s motivation for rejecting Yeasts’ marriage proposal was her intimate understanding of the poet’s talent? The prevailing consciousness of the eccentricities of most committed poets stirred her unwillingness to come in-between Yeats and his calling—an empathetic resolve to let him commit himself solely to his most excellent Muse. Should we now re-imagine our judgment of Maud Gonne’s act essentially as her inability to identify real love? I think we should begin to accommodate an alternate conversation able not only to confront intellectually and humanly the gross malignity meted out against Maud Gonne, but also to put forward a groundbreaking, honest portrait of Maud Gonne’s love for Yeats.

Brigitte: That may be because she envisioned his Muse as a feminine entity. The Muse is not a person. Being devoted to writing should not be an exclusive passion. On the contrary, being preeminently committed to poetry can enhance a deeper love relationship. Poetry and love feed on each other. But I agree with you, we need newer perspectives and diverse voices.

Darlington: Maybe I should marry a poet. But before then, let me focus on you now. You were born and brought up in France, surrounded by many excellent European books, but you have just mentioned that as a child you were enthralled by stories about Africans and Indians, what kind of stories were they, and to what extent did they help in shaping you into a poet and poetry lover whose interest in African poetry is too alive, too admirable and able to move beyond the pages of books, focusing also on publishing and literary recognition in terms of giving prizes?

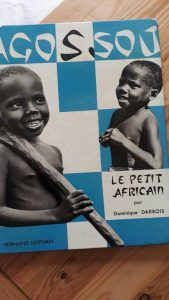

Brigitte: I’ve found photos with African and Indian friends of the family my dad took from my birth. These people were friends of the family at a time when Africans did not travel to Europe so much. You never recover from such an early fascinating influence. My dad would read us Rudyard Kipling every evening. I still treasure this book in my own library.

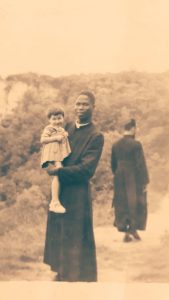

Then I read all kinds of books about African kids. My mum’s brother spent forty years in Dahomey/Benin and when he came over, he’d tell us stories about Africa. Then coincidentally I was asked to give talks about apartheid during my higher education time. I was preparing admission into one of those illustrious French schools. And later on, my students asked me no less than paying a visit to South Africa so I could bring them firsthand testimony of the situation down there. And so on and on. By the way, the tall handsome man on the photo was a cardinal. He was close to Pope John Paul II.

Darlington: The experiences you just referred to are memorable. I would appreciate it, if you could comment freely on Europe’s perception of Africa, especially Africa’s literary culture. It was this that the legendary Chinua Achebe hoped to address in “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness“, his very provocative and phenomenal 1975 Chancellor’s Lecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Through exegetic sentential and allegorical analysis of Heart of Darkness, Achebe respectfully but fearlessly asserted that both Conrad and his character Marlow are desperately racist and, in many ways, represent Europe’s hatred for Africa. Three decades later, Chimamanda Adichie initiated a similar conversation in her TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story”, in which she pointed that Europe had chosen only a side of Africa that fits into her misleading narrative, chosen to see a people ravaged by hunger and war, but are blind both to the industry of her talented sons and daughters and even to her (Europe’s) role in under-developing Africa. Late last January, during a Q&A at La Nuit des Idées, a Parisian cultural festival, the Nigerian author and guest of honour Chimamanda Adichie was asked by a French journalist, Catherine Broue, whether Nigeria “had any bookshops”. “When people talk about Nigeria”, she tried to clarify, “it’s about Boko Haram, it’s about violence, it’s about security. I should like you to tell us something about Nigeria which is different…and that is why I’m saying are there bookshops? Of course I imagine there are”. Adichie’s response was direct: “You know I think it reflects very poorly on French people that you’ve had to ask me that question…surely, it’s 2018. I mean, come on. My books are read in Nigeria. They’re studied in schools, not just in Nigeria but across Africa and it means a lot to me”. I wonder how well we are today.

Brigitte: When in South Africa I managed to buy papers from the townships to get information. I sent them poems and surprisingly enough they published me. I believe they were stunned I could write such poems. Shortly afterwards I received a long letter from a Tshwane writer who now is a doctor in literature there. He invited me on the social networks and then it was an explosion. With poets, we made poetry anthologies and now with WordsRhymes&Rhythm, we offer contests. I have read Achebe. I have heard about that interview. I, here, belong to a group of authors in this part of France that has had to suffer so much from French hubris. The French in general know nothing about Africa. When I told my mum in law I was going to South Africa, she asked: “Yes, but in which country in South Africa?” I believe many French people have stopped showing interest when African countries conquered their independence. And they only keep in mind that these countries are far below our standard of living. Also what ruins their vision of Africa is the flood of illegal immigration which is indeed a national problem. So they prefer to ignore what’s going on “down there.” Does it come as a surprise then that you often face faceless people if you speak of Africa? Even in this part of France, you should see the countenance of such ignorami when I show them the books published in Lagos, during our literary salons. Most walk past without even casting a glance. I work here all on my own. No one is interested. I must admit the language barrier is a huge one. At best people may show interest in the countries belonging to the former French speaking colonies known as francophony. But the English speaking countries remain outside their sphere of interest. Niger? They will ask when they hear of Nigeria. There’s still a long way to go. When I tell people the level of your universities is practically to be rated above ours, they look blank or laugh. Except a few open minded friends and family, fortunately.

Darlington: Yes. And honestly, I’m in awe of your commitment to African literature, Nigerian poetry in particular, and your humility in remaining locally rooted even as you aim so globally. I’ve watched for some years now as you invest your talent, time and finance to promote poetry in Nigeria through opening a publishing house that caters for the needs of energetic brilliant young Nigerian poets, and even the monthly Brigitte Poirson Poetry Prize that has motivated many younger poets who have come to realize that the world is actually interested in their words, and that that world could be anyone. Can you intimate me about the vision, accomplishments and challenges of WordsRhymes&Rhythm? And again, may I ask, what is it you find in young Nigerian poets that you think are impossible to overlook?

Brigitte: It’s very simple. Mr Kukogho, I like to call him sir KIS, whom I had recruited for a South African anthology, manifested so much talent and dedication that I suggested he should create a publishing house. It turned out he had nothing else in mind. We both marveled at the knowledgeable talents of young Nigerian writers on the social networks. They were able to improvise poetic jewels, would throw one another the gauntlet in competitions. And they craved for recognition in a very harsh environment. The situation in the life of many, even holding diplomas, is inversely proportional to their talents. I thought I could help in a little way.

Darlington: Tremendous, I must commend, best describes your achievements. Also, the pioneer Nigerian poets like: Gabriel Okara and JP Clark, poets of the not so old generation, the likes of: Niyi Osundare, Tanure Ojaide and Odia Ofeimun, the generation of Ezenwa Ohaeto and Esiaba Irobi, and that of Uche Peter Umez and Ikeogu Oke have succeeded very admirably to pitch their talent at a global level, do you find that kind of promise in younger Nigerian poets?

Brigitte: Oh definitely! Ayoola Goodness Olarewanju, Aremu Adams Adebisi, Mbagu Valentine, Soonest Nathaniel Scholes, Michel Ace—who spurs mind into creativity, Shittu Fowora, Alfred Joseph, Tukur Loba Ridwan, Ngozi Olivia Osuoha, Ogedengbe Tolu Impact. These are a handful of names that spontaneously come to my mind. But there are many more. They are promising poets. Some have been published or have won prizes or contests. In prose I’ve been accompanying some gifted young men: Nonso Anyanwu, Ifeanyichukwu Peter Eze, Chukwuebuka Ibeh and more. The ladies are quite shy. Last year we decided that the May contest would be reserved to the female poets to give them a fair chance. They proved good.

Darlington: Congregated in your list are beyond doubt notable writers. I should quickly add to that list names like: Chibuihe Obi, Romeo Oriogun, Frank Eze, Ehi’zogie Iyeomoan and Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto—these poets create words capable of accompanying the dead to great rest; short-story writers like: Dera Duru, Arinze Ifekandu, Ilo Chizaram, Caleb Somtochukwu, Chimee Adioha, Chinwendu Nwangwa and Jennifer Emelife—they’d hold your emotions spellbound until you finally give up, like surrendering your life to Christ, before a demeaning priest; electrifying performance-poets like: Dike Chukwumerije, Graciano Enwerem and Ebo Flora Nwannediuto; editors like: Otosirieze Young-Obi of Brittle Paper, John Light-House Oyewale of Praxis Magazine, Basit Jamiu of Enkare Review and Chimezie Chika of Ngiga Review—peerlessly innovative young men. Even words are mindful of their limitation to describe how gifted and well-informed these young men and women are.

Brigitte: Splendid! This is Nigeria, the home of words.

Darlington: You’re full of kind words, Brigitte. Here, all we do is to chase words, hoping they don’t turn back and begin to chase us.

Brigitte: Words chasing writers? That’d be epic! Honestly.

Darlington: We’d wait till then. But, for now, speaking of women, does it not worry you that feminism has been misunderstood in many quarters, and even more disappointingly by women? My idea of a feminist is that trader who scolded her neighbor (in the market) for asking me, “Sir, this one you’re buying big tubers of yams, did your wife give birth? I know it must be a son”. The woman, obviously upset by what she heard, rebuked her neighbor. “Must the child be male to deserve good things?” she asked. “Is it not the same pain we feel while giving birth to boys that we endure during the birth of girls? Or is there a different vagina for producing sons?” Frankly, I was startled by the unexpectedness of the conversation and moved by the insight of that daring woman that I couldn’t tell them I was a legitimate bachelor, with a badass husband material. If only I realized in time the impact of such fatherzoning. How, I would like to know, have the younger Nigerian poets, whose work you’ve read, reacted to the feminist movement?

Brigitte: I’ve chatted with many a poet that referred to Adam’s rib to explain why women should better remain submissive. Many point to women as the source of every problem in failed marriages and relationships. I had to explain that women are not possessions. Marriage is a mutual bond between two equal partners, even if the distribution of the tasks is different. They have complementary roles on an equal footing. Many young poets have evolved positively. But you know there’s still a long way to go here too. Women are often discriminated against in their professional lives. Inequality is often more surreptitious here, more openhearted in the Nigerian poets. I’ve recently struggled hard with a young Muslim poet who wanted to be edited. But I said I couldn’t condone his vision of womanhood. He advocated women to be veiled and behave like true possessions of their husbands. I referred him to the Qur’an to prove he was wrong. He admitted it, but to date has been unable to offer another vision.

Darlington: Should we then say that religious indoctrination and fanaticism are among human’s gravest obstacles? But does it also mean that education has not fully succeeded in transforming human lives? And can literature humanize us where everything else has failed?

Brigitte: Ideologies are the worst plagues of the human mind. And among them I rank ultra-liberalism. It’s destroying the earth and the living creatures. Yes, indoctrination, when addressed to young minds in particular, is deadly. Education is not properly armed to fight all this. All we can do as teachers is to try to open the eyes by setting a personal example as a reference. Or offer legal and moral references. I remember a group of young students aged around sixteen and seventeen telling me about the first lady. (She’d been a top model). I stared at them blankly. “I don’t know about any first lady”, I asserted sternly. They looked stunned and some girls giggled. Then I told them that if we read the constitution properly, there are no citizens above others. We are all equal. “Do you know what equal means?” I asked. “It means everyone in the nation is first.” There’s no such thing as a first lady. If there’s one, then there must be a last, and then, I claim to be that last. I still remember their smile at the end of my diatribe. They felt incredibly relieved. It opened vistas they said they’d never imagined before. It’s a personal responsibility to educate minds, even when you’re supposed to teach the technicalities of language. Literature as a whole is among the most appropriate tools to reach that goal. It’s a tool, like the legal system. But words are nothing as such, if we don’t put our souls into personally transmitting values.

Darlington: Brilliant. Yes, I think it behooves on us as teachers and writers to light up the path of our society. Do you know I never get tired of chatting, speaking or listening to someone talk about teaching? It will be thrilling to have you share some of your thoughts on creative teaching when next I have the fortune of engaging you. I’d be here.

Brigitte: I noticed it’s a Nigerian habit to use a conditional “I’d be there” when a future is expected.

Darlington: Almost a canon, a reaffirmation of hope in what would be.

Brigitte: Exactly. I think it’s an interesting way to express it. A very African way to render the idea. The future is the basic tense of expectation. It even disappears into a present that better expresses certainty after conjunctions such; “as when” and “as soon as”. These events are presupposed to be as good as done. But using the tense usually in expressing a hypothetic fact to reaffirm hope is much more complex. It’s a mixture of hope, expectation and mild trust.

Darlington: You have a unique startling way of connecting ideas with words. It’s a beautiful thing. And while expressing that connectedness, you transcended the possible reaches of mortality, ascending into labyrinths that stretch beyond the imagination. Yes, the future is elusive and unable to be pinned down, but through words, and a mixture of hope, we create a future impossible of eluding us.

Brigitte: Absolutely! You have put it rightly and magnificently. Writing and teaching share in common this urge to create awareness and open new vistas in people’s minds. Yes, teaching is the act of giving people the right tools with which they will be able to build up their lives.

Darlington: All I see now are beings wearing new a form, becoming human again. Thank you, Brigitte, for sharing these words with me.

Brigitte: The pleasure is mine, Darlington.

(Interview has previously appeared on NGIGA review has gotten Black Boy Review has the permission to republish herein)